In a recent talk at Cornell University, Peter Kareiva, chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy, argued that environmentalists need to move away from the traditional “doom and gloom” message. “I don’t want to manage the decline of the planet,” he said. Instead, Kareiva would like environmentalists to promote hopeful messages, reorient conservation projects, and reconnect with the public.

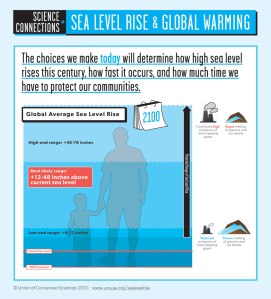

Some of the doomiest and gloomiest messages have to do with the perils of sea level rise. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that sea levels will rise 7 inches to 2 feet between 1990 and 2100. The rise in sea levels is linked to three processes: thermal expansion (when water heats up, it expands), melting of glaciers and polar ice caps, and ice loss from Greenland and West Antarctica.

A particularly gloomy infographic of a father and child underwater

Researchers from the World Bank and elsewhere suggest that the effects of sea level rise will disproportionately affect developing countries and the poor. Such predictions have led environmentalists to advocate for the interests of “conservation refugees”: people who will have to leave their homes and communities because of the effects of climate change and global warming. A recent Nature Climate Change article contends that the impacts of sea level rise “are potentially severe, implying a conceivable risk of forced displacement of up to 187 million people within this century.”

But why focus on possible future catastrophes? Poverty, displacement, and natural disasters are problems today. As phenomenon they are not contingent on sea level rise.

Even if we could accurately predict future climate states, could we predict future modes of governance? Is it inevitable that dynamic shorelines will lead to political instability?

This Google maps image, north of Vicksburg, Mississippi, shows the shape of the Mississippi River in 2013.

This 1944 map from Geological Investigation of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River shows the location of the Mississippi for the past 1,000 years. Each color represents an old channel.